Ad

Skin cancer

Application to facilitate skin self-examination and early detection. read more.

What is it melanoma?

Melanoma is a potentially serious type of skin. Cancer, in which there is an uncontrolled growth of melanocytes (pigment cells). Melanoma is sometimes called evil one melanoma.

Melanoma management is evolving. For updated recommendations, see the Australian Cancer Council's Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Melanoma.

Melanocytes

Normal melanocytes are found in the basal cap of the epidermis (the outer layer of the skin). Melanocytes make a protein called melanin, which protects skin cells by absorbing ultraviolet rays (UV) radiation. Melanocytes are found in equal amounts on black and white skin, but melanocytes on black skin produce much more melanin. People with dark brown or black skin are much less likely to be harmed by UV radiation than those with white skin.

Noncancerous growth of melanocytes produces moles (properly called benign melanocytic naevi) and freckles (ephelides and lentigines) The cancerous growth of melanocytes produces melanoma. Melanoma is described as:

- In the place, if a tumor is limited to the epidermis

- Invader, if a tumor has spread to the dermis

- Metastatic, if a tumor has spread to other tissues.

Who gets melanoma?

The highest reported rates of melanoma in the world are in Australia and New Zealand. About one in 15 white-skinned New Zealanders is expected to develop melanoma in their lifetime. In 2012, invasive melanoma was the third most common cancer in men (after colorectal and prostate cancers) and in women (after breast and colorectal cancer).

Melanoma can occur in adults of any age, but it is very rare in children. In New Zealand in 2012:

- 1% occurred in children under 24 years of age

- 10% occurred in people ages 25 to 44.

- 38% in people aged 45 to 64

- 25% in people from 65 to 74 years old

- 27% in people over 75 years of age.

According to New Zealand Cancer Registry data, 2,366 invasive melanomas they were diagnosed in 2013; The 53% were in men. There were 354 melanoma deaths in 2012 (63% were men).

The main risk factors for developing the most common type of melanoma (superficial spreading melanoma) include:

- Increasing age (see above)

- Previous invasive melanoma or melanoma in situ

- Basal anterior or scaly cell carcinoma

- Many melanocytic (lunar) nevi

- Multiple (> 5) atypical nevi (large or histologically dysplastic moles)

- A strong family history of melanoma with 2 or more affected first-degree relatives

- White skin that burns easily

- Parkinson's disease.

These risk factors are not relevant for rare types of melanoma.

What causes melanoma?

Melanoma is thought to start as uncontrolled proliferation of melanocytic stem cells that have undergone genetic transformation.

Superficial forms of melanoma spread within the epidermis (in situ). A pathologist you can report this as the radial or horizontal growth phase.

Other genetic changes promote a tumor to invade through the basement membrane into the surrounding dermis when it becomes an invasive melanoma.

Nodular Melanoma has a vertical growth phase, which is potentially more dangerous than the horizontal growth phase. It can arise within a previously healthy dermis or within the invasive portion of a more superficial pre-existing type of melanoma.

Once melanoma cells have reached the dermis, they can spread to other tissues through the lymphatic local system lymph nodes or through the bloodstream to other organs such as the lungs or brain. This is known as metastatic disease or secondary spread. The chance of this happening depends mainly on how deep the cells have penetrated the skin.

Precursor injuries

Melanoma can arise from normal-looking skin (in about 75% of melanomas) or from a mole or freckle, which begins to grow and change in appearance. Precursor injuries include:

-

Benign Melanocytic nevus (normal mole)

-

Atypical or dysplastic nevi (funny-looking mole)

- Atypical lentiginous junction nevus (flat nevus on skin badly damaged by the sun) or atypical solar lentigo

-

Large or giant size congenital melanocytic nevus (brown birthmark).

What are the clinical features of melanoma?

Melanomas can appear anywhere on the body, not just in areas that get a lot of sun. In New Zealand, the most common site in men is the back (about 40% for melanomas in men), and the most common site in women is the leg (about 35% for melanomas in women).

Although melanoma usually starts as a skin injury, it can also rarely grow in mucous membranes like lips or genitals. Occasionally it occurs in other parts of the body, such as the eyes, brain, mouth, or vagina.

First sign A melanoma is usually a freckle or mole that looks unusual. Melanoma can be detected at an early stage when it is only a few millimeters in diameter, but it can grow to several centimeters in diameter before being diagnosed.

- A melanoma can be in a variety of colors including tan, dark brown, black, blue, red, and occasionally light gray.

- Melanomas that lack pigment are called amelanotic melanoma.

- There may be areas of regression that's the normal skin color, or white and marked.

During its horizontal phase of growth, a melanoma is normally flat. As the vertical phase develops, the melanoma thickens and rises.

Some melanomas are itchy or tender. More advanced injuries can easily bleed or Cortex finished.

Most melanomas have characteristics described by the Glasgow 7-point checklist or by the ABCDE criteria for melanoma. Not all injuries with these characteristics are malignant. Not all melanomas show these characteristics.

Glasgow 7 Point Checklist

Main features

- Size change

- Irregular shape

- Irregular color

Minor features

- Diameter> 7mm

- Inflammation

- Oozing

- Change in feeling

The ABCDE of melanoma

An asymmetry

B edge irregularity

C color variation

D diameter greater than 6 mm

E Evolving (expanding, changing)

See ABCDE criteria.

Melanoma subtypes

Conventional classification

Melanomas are described according to their appearance and behavior. Those that start out as flat patches (i.e. have a horizontal growth phase) include:

- Superficial spread melanoma

-

Lentigo maligna melanoma and lentiginous melanoma (in sites damaged by the sun)

- Acral Lentiginous melanoma (on the soles of the feet, palms of the hands, or nail)

These superficial forms of melanoma tend to grow slowly, but at any time, they can begin to thicken or develop a nodule (that is, advance to a phase of vertical growth).

Melanomas that rapidly involve deeper tissues include:

- Nodular melanoma

- Spitzoid melanoma

- Mucous membrane melanoma

- Neurotropic and desmoplastic melanoma

- Spindle cell melanoma

- Ocular melanoma.

Combinations may arise, for example, nodular melanoma arising within a superficially extending melanoma, or desmoplastic melanoma arising underneath a malignant lentigo.

Classification by age, sun exposure and number of snow

Melanoma is also classified according to its relationship to sun exposure, age, and the number of melanocytic nevi.

Childhood melanomas (under the age of ten)

- Extremely rare

- Infrequently associated with excessive sun exposure

- Compared to melanoma in adults, they are more often amelanotic (flesh-colored, pink or red), nodular, bleeding and ulcerated.

- May arise within giant congenital melanocytic nevi> 40 cm in diameter

Early-onset melanomas

- More common in women than men.

- The most common clinical subtype is superficial spread.

- Associated with many melanocytic nevi

- They tend to be seen on the lower limb

- Tends to have BRAFV600E genetic mutation

- Associated with intermittent sun exposure

Late-onset melanomas

- More common in men than in women.

- The most common clinical subtype is lentigo maligna.

- They often occur on the head and neck.

- Associated with lifetime cumulative sun exposure.

Melanoma is usually epithelial originally, that is, starting on the skin or, less frequently, mucous membranes. But very rarely, melanoma can start in an internal tissue like the brain (primary CNS melanoma) or the back of the eye (see ocular melanoma).

Melanoma images

Superficial spread melanoma

Typical SSMM

SSMM with regression

Amelanotic melanoma

More images of superficial spread melanoma

Lentigo malignant melanoma

Lentigo malignant melanoma

Evil lentigo

Nodular melanoma in lentigo maligna

More images of lentigo maligna melanoma

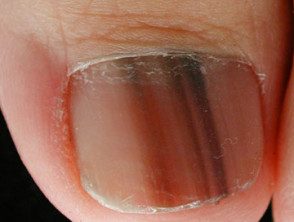

Acral lentiginous melanoma

Acral lentiginous melanoma

© Dr. Ph Abimelec -

Amelanotic subungual melanoma

More images of acral lentiginous melanoma

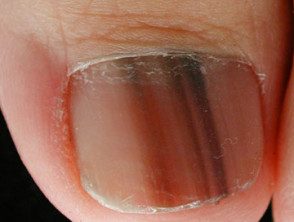

Melanoma of the nail unit

Melanoma of the nail unit

Melanoma of the nail unit

Melanoma of the nail unit

More pictures of nail unit melanoma

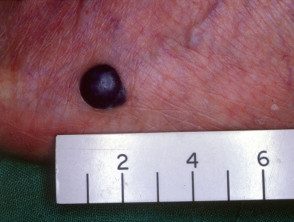

Nodular melanoma

Black nodular melanoma

Amelanotic nodular melanoma

Ulcerated Nodular Melanoma

More Nodular Melanoma Images

How is melanoma diagnosed?

Melanoma can be suspected due to the clinical characteristics of an injury or due to a history of changes. The dermoscopic appearance is useful in the diagnosis of early melanoma without features. Some melanomas are extremely difficult to recognize clinically.

The suspicious lesion is surgically removed with a clinical margin of 2 to 3 mm to pathological examination (diagnosis excision) A partial biopsy It is best avoided, but can be considered in large injuries.

The pathological diagnosis of melanoma can be very difficult. Histological The characteristics of the melanoma of superficial propagation in situ include the presence of buckshot (pagetoid) dispersion of atypical melanocytes within the epidermis. These cells can be enlarged with unusual nuclei. Dermal invasion produces melanoma cells within the dermis or deeper into subcutaneous grease.

Immunohistochemical staining may be necessary to confirm melanoma.

Pathology report

The pathologist's report must include a macroscopic description of the specimen and melanoma (naked eye) and a microscopic description. The following characteristics should be reported if there is invasive melanoma.

- Diagnosis of primary melanoma

- Breslow thickness to the nearest 0.1 mm

- Clark's invasion level

- Excision margins (the normal tissue around a tumor)

- Mitotic rate - a measure of how fast cells are proliferating

- Whether or not there is ulceration

The report may also include comments on the cell type and its growth pattern, invasion of blood vessels or nerves, inflammatory response, regression and if there are associated in the place disease and associated nevi (original mole).

What is the thickness of Breslow?

Breslow thickness is reported for invasive melanomas. It is measured vertically in millimeters from the top of the granular layer (or base of superficial ulceration) to the deepest point of tumor involvement. It is a strong predictor of results; the thicker the melanoma, the more likely it is that metastasis (spread).

What is Clark's level of invasion?

Clark's level indicates the anatomical plane of the invasion.

- Level 1: melanoma in situ

- Level 2: melanoma has invaded the papillary dermis

- Level 3: melanoma has filled the papillary dermis

- Level 4: melanoma has invaded the lattice dermis

- Level 5: melanoma has invaded subcutaneous tissue

Deeper Clark levels are at increased risk for metastasis. It is useful to predict the outcome in thin tumors. It is less useful than Breslow thickness for thick tumors.

What is the treatment for melanoma?

Upon confirmation of the diagnosis, a wide local excision is made at the site of the primary melanoma. The extent of the surgery depends on the thickness of the melanoma and its location. The recommended margins in New Zealand (2013) are shown below.

- Melanoma in situ: 5 - 10 mm

- Melanoma <1 mm: 10 mm

- Melanoma 1–2 mm: 10-20 mm

- Melanoma> 2mm: 20mm

The Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Melanoma (Australia) updated in 2017 recommend, where possible:

- Melanoma in situ: 5 mm, and wider margins if applicable

- Melanoma <1 mm: 10 mm

- Melanoma 1–2 mm: 10-20 mm

- Melanoma 2–4 mm: 10-20 mm

- Melanoma> 4mm: 20mm

Staging

Staging melanoma means finding out if melanoma has spread from its original place on the skin. Most melanoma specialists refer to the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) cutaneous Melanoma staging guidelines (8th edition, 2018). In essence, the stages are:

| Stage | Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Stage 0 | Melanoma in situ |

| Level 1 | Thin melanoma <2 mm de espesor |

| Stage 2 | Thick melanoma> 2 mm thick or> 1 mm thick with ulceration |

| Stage 3 | Disseminated melanoma to involve local lymph nodes |

| Stage 4 | Distant metastasis have been detected |

Should the lymph nodes be removed?

If the local lymph nodes are enlarged due to metastatic melanoma, they must be completely removed. This requires a surgical procedure, generally in general. anesthetic. If they are not enlarged, they can be analyzed to see if there is microscopic spread of the melanoma. The test is known as a sentinel node biopsy.

In New Zealand, many surgeons recommend sentinel node biopsy for 1 mm thicker melanomas, especially in younger people. However, although biopsy can help stage cancer, it does not offer any survival advantage.

Lymph nodes containing metastatic melanoma often enlarge rapidly. An involved node is generally not sensitive and has a firm to hard consistency.

If melanoma is extended, treatment is not always successful in eradicating cancer. Some patients may be offered new or experimental treatments, such as:

-

Immunotherapy: interleukin-2, interferon alpha 2b

- BRAF inhibitors: dabrafenib and vemurafenib

- MEK inhibitors: trametinib

- Combined BRAF and MEK inhibitors: dabrafenib

- C-KIT inhibitors: imatinib, nilotinib

- CTLA-4 antagonist: ipilimumab

- PD-1 lock antibodiesnivolumab, pembrolizumab

What happens at the follow-up?

The main objective of follow-up is to detect recurrences early (metastatic melanoma), but it also offers the opportunity to diagnose a new primary melanoma at the earliest possible opportunity. A second invasive melanoma occurs in 5–10% of melanoma patients and a new melanoma is diagnosed in situ in more than 20% of melanoma patients.

The Australian and New Zealand Melanoma Management Guidelines (2008) make the following recommendations for the follow-up of patients with invasive melanoma.

- Self-examination of the skin

- Routine skin checks by the patient's preferred healthcare professional

- Follow-up intervals are preferably semi-annually for five years for patients with stage 1 disease, quarterly or quarterly for five years for patients with stage 2 or 3 diseases, and annually thereafter for all patients.

- Individual patient needs should be considered before offering adequate follow-up

- Provide education and support to help the patient adjust to his illness.

Follow-up appointments can be made by the general practitioner and the patient's specialist.

Follow-up appointments may include:

- A check from the scar where the primary melanoma was removed

- An idea of regional lymph nodes

- A general examination of the skin.

- A complete physical exam

- In those with many moles or atypical moles, base Whole body images and sequential macro and dermoscopic images of melanocytic lesions of interest (mole mapping).

In those with more advanced primary disease, follow-up may include:

- Blood tests, including LDH

- Images: ultrasoundX-rays Connecticut, Magnetic resonance and PET scan.

Testing is not worthwhile for patients with stage 1 or 2 melanoma unless there are signs or symptoms of the disease reappearance or metastases No tests are needed for healthy patients who have been well for 5 years or more after the removal of their melanoma.

What is the prognosis for melanoma patients?

Melanoma in situ heals by excision because it has no potential to spread throughout the body.

The risk of spread and final death from invasive melanoma depends on several factors, but the main one is the Breslow thickness of the melanoma at the time of its surgical removal.

Metastases are rare for melanomas. <0.75 mm and the risk for tumors 0.75–1 mm thick is about 5%. The risk steadily increases with thickness so that melanomas> 4 mm have a risk of metastasis of around 40%.